Two Legs of the Same Compass: Freemasonry in Belgium and the Netherlands

In Belgium there are approximately ten thousand Dutch-speaking members of a Masonic lodge; the Netherlands counts some seven thousand Freemasons. While the Netherlands mainly looks at the Anglo-American tradition, Belgium adheres to the French or ‘liberal’ tradition. Jozef Asselbergh, former Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Belgium, outlines the historical development and differences between Freemasonry in the north and south.

Does this analysis on the differences between Freemasonry in the Netherlands and Belgium give us a better understanding of the broader cultural contrasts between north and south? Or rather, does it amplify the lack of understanding? First, a closer look at the subject: Freemasonry, a bastard child of the Reformation, relates to a philosophy of life, but is not a religion or a substitute for religion. Freemasonry has no creed, and therefore, nothing like a Credo in unum Deum or a public confession of faith.

Freemasonry builds on faith in the possibility of a mutual friendship among people of different philosophical or political backgrounds; the practice is focused on tolerance, an open and trustworthy mutual relationship with discretion as a logical result. There is minimal hierarchy: within the lodge, it is limited to ensuring an orderly gathering, and for the lodgers, within the same context, to respecting agreements they have made among themselves as members of a ruling body (or obedience).

Freemasonry offers its participants an adequate forum for the development of their philosophy of life. The churches have understood the latter, especially Rome; they accuse the order of indifferentism, the belief that no one religion is superior to another.

Orthodox and liberals

Worldwide, there is a schism in Freemasonry between a large majority that follows English orthodoxy and a minority regarded essentially as liberal and geographically as Latin. The first is exclusively male. Obtaining and maintaining recognition from the United Grand Lodge of England presupposes the belief in a supreme being, who, in Masonic language, is referred to as the Great Architect of the Universe, and whose will is enshrined in a holy book such as the Bible or Koran. Liberal Freemasonry also has mixed or female lodgers, makes no requirements regarding beliefs, and the symbols relating to a god or his revelation are not always present at meetings. Both branches distance themselves from religious and political subjects; rituals, rules of conduct and hierarchy are very similar.

Johannes Henderikus Morriën, Allegory of Freemasonry, circa 1850, Rijksmuseum

Johannes Henderikus Morriën, Allegory of Freemasonry, circa 1850, Rijksmuseum© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Flanders and Brussels count 141 Dutch-speaking lodges under six obediences (two of which are exclusively male and one exclusively female); the number of Dutch-speaking members is approximately ten thousand (moreover, the French-speaking Brussels lodges have an unknown number of Dutch-speaking members). Only one obedience with 25 Dutch-speaking lodges and seven hundred members belongs to the Anglo-American branch; the other five, with more than nine thousand members, belong to the liberal branch.

The Netherlands has about two hundred lodges with just over seven thousand members. 165 lodges with six thousand members are affiliated with the Grand Orient of the Netherlands, which belongs to the Anglo-American tradition. This obedience, the oldest in the world, also has lodges overseas, in Suriname, Zimbabwe and the Caribbean. The other lodges are predominantly mixed and divided among five umbrella organisations. Six lodges work independently of any connection.

From the beginning, in the first half of the eighteenth century, the developments in north and south were different

For the majority of Dutch Masons, the concept of a Great Architect of the Universe is determined by reason, from God to an ordering principle. The vast majority of Flemish Freemasons are liberal humanists, although faith is no longer a requirement. In terms of the political spectrum, Dutch members are mostly liberal; Flemish lodges are predominantly “purple” (liberal democratic and social democratic), with notable differences from lodge to lodge.

The main difference within Freemasonry in the Low Countries corresponds with the previously outlined division between “Regular Freemasonry”, which follows English orthodoxy, and Liberal Freemasonry. These labels may have originated during the course of the nineteenth century and were established during the Cold War, but from the beginning, in the first half of the eighteenth century, the developments in north and south were different. This had everything to do with a different political status. When Freemasonry emerged at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the north was an independent republic while the Southern Netherlands was largely under Austrian rule (except for the Prince-Bishopric of Liège and the Duchy of Bouillon). In the Dutch Republic, the Calvinist Dutch Reformed Church was privileged, but a tolerant climate left room for other denominations, as long as they practised in secret. The south was Catholic; when Protestants and Jews were allowed to openly profess their faith in 1781, even that became a reason for opposition. The Southern Netherlands, Antwerp, in particular, also served as Rome’s lookout for the small and unruly Protestant nation.

The Dutch Republic’s English connection

An intensive exchange existed between the United Kingdom and the Republic, both Protestant nations: politicians, intellectuals and scholars maintained regular contact. Stadtholder William III of Orange – as William III, King of England and Ireland – consolidated the political dominance of the Protestants; Dutch scientists Willem Jacob ’s Gravesande and Christiaan Huygens became members of the newly-founded Royal Society of Natural Knowledge. John Theophilus Desaguliers, one of the founding fathers of Freemasonry and right-hand man of Isaac Newton, wrote a foreword for the English translation of a theological work by Bernard Nieuwentyt and gave some thirty lectures in the Dutch Republic in support of their shared theistic vision as opponents of Spinoza.

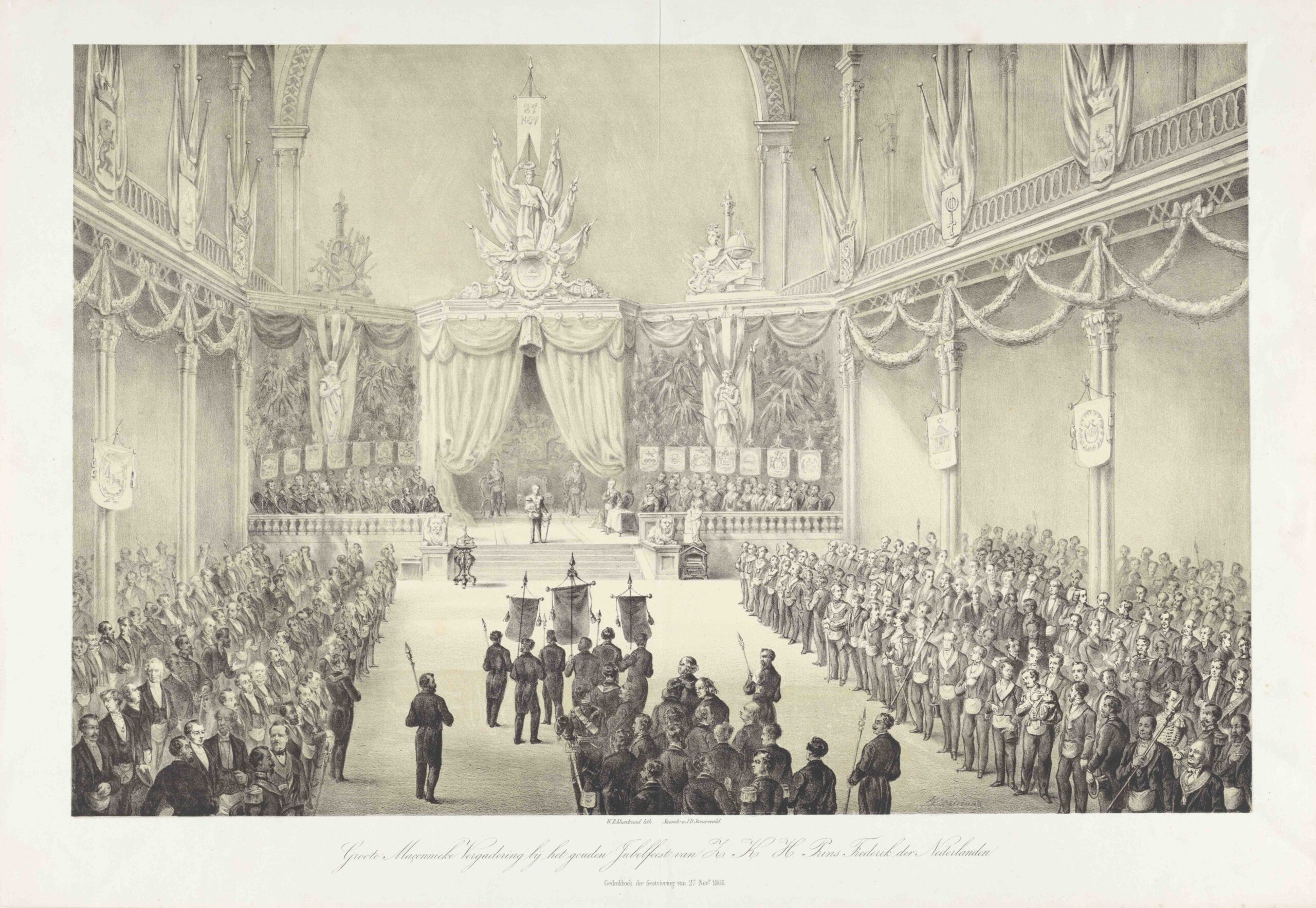

Willem Bernardus IJzerdraat, Grand Maçonnique Assembly at the Golden Jubilee Celebration of H.R.H. Prince Frederik of the Netherlands, 1866-1867, Rijksmuseum

Willem Bernardus IJzerdraat, Grand Maçonnique Assembly at the Golden Jubilee Celebration of H.R.H. Prince Frederik of the Netherlands, 1866-1867, Rijksmuseum© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Theism, deism, unitarians, trinitarians

Not only was there dispute among the different Protestant denominations, but at the end of the seventeenth century and beginning of the eighteenth century, other theological matters became the subject of discussion, especially after Spinoza’s publications. Belief in God was not a subject (even though there were some atheists, in the modern definition of the word), but rather the interpretation of the concept of God.

To the theists, He was not only the Creator, but He was perpetually directing creation, sometimes as reward and sometimes as punishment for the behaviour of mankind. For the deist, God had withdrawn after creation and intervened only as a rare exception; for example, when things threatened to go awry, hence the image of clockmaker, the invisible hand.

Then there was also dispute over a singular God (unitarians) or a triune God: the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit (trinitarians). If adherents of these doctrines were at odds in the outside world, they came together in the lodges. Needless to say, these kinds of discussions passed the Catholic south by.

The Dutch Republic was quick to embrace Freemasonry

It is no wonder, then, that the Dutch Republic was quick to embrace Freemasonry. Before there was even mention of a Dutch version, English visitors and expats held sporadic lodge meetings in The Hague and Rotterdam. This English connection also had drawbacks, as opponents of the stadtholder suspected Freemasonry of having a political agenda. This led to a ban in 1735.

On 26 December 1756, the Grand Orient of the Netherlands was founded, an umbrella organisation that, among other things, ensures compliance with the Constitution (outlining the mutual regulations of the lodges) and that accepts or rejects newly established lodges. In 1770, the Premier Grand Lodge of England acknowledged the independence of the Grand Orient of the Netherlands, thus making it the largest obedience in the world. (The United Grand Lodge of England only dates from 1813.)

Dutch lodges were mainly populated by members of minority groups, dissenters: Remonstrants, Catholics, Lutherans, Anabaptists. Socially, they were representatives of the petty nobility and the rising bourgeoisie. After the failed liberal revolution of 1787, a number of them fled to France and established a lodge in Dunkirk.

Ancien Régime in the South

The evolution was completely different in the Southern Netherlands: there was no privileged contact with England, no exchange of intellectuals or scientists and no religious diversity. The north showed signs of modern political activity, yet the south was still anchored in the Ancien Régime. While the lodges in the north formed a connection, that was not the case in the south. Lodges arose with a focus on the Premier Grand Lodge of London, as in Bruges, for example; there were military lodges set around the barracks of foreign armies with garrison rights (Dutch in Lillo, Scots in Namur); and lodges were also established in France (Mons). The success of Freemasonry in the south is somewhat paradoxical, given the hostile criticism from Rome.

Rome did not appreciate an initiative that brought together men of different persuasions around a life philosophy, without the authority of a church leader

What’s certain is that the churches in general – and Rome, specifically – did not appreciate an initiative that brought together men of different persuasions around a life philosophy, without the authority of a church leader. Two encyclicals (In Eminenti, dating to 1738 and Providas, dating to 1751) condemned Freemasonry and prohibited Catholics from joining or attending meetings. The first and most serious reproach concerned exactly what Freemasonry upheld: bringing together people of different denominations. So why did Catholics (including priests and bishops) join anyway? Because during the Ancien Régime, whether in Paris, Madrid or Vienna, the monarch decided whether or not papal bulls were distributed. This privilege was not granted to the aforementioned decrees. The reason is obvious: nobility and clergy, who initially played a predominant role in the lodges, were not keen on having their new club taken away.

The population of these lodges, unlike that of the north, was socially rather conservative. This changed somewhat after the Act of Tolerance (1781) when Protestants and the bourgeoisie could easily join. At the beginning of 1786, Joseph II reduced Freemasonry to three lodges … and to Brussels.

Revolutions and occupation

Thanks to a great talent for diplomacy and conciliation, Dutch Freemasonry managed to emerge through the turbulence of the Patriot Revolution, the Batavian Republic and the French annexation unscathed. The aversion towards French Freemasonry, however, grew when the Dutch lodges, after the political annexation by Napoleon, were required to join the Grand Orient de France.

Things went differently in the Southern Netherlands, which was annexed immediately after the invasion by France in the 1790s. Four lodges which had survived the turmoil of war and revolution – three from Wallonia, one from Brussels – were recognised by the Grand Orient de France during the French reign, new lodges were founded, and the bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie made their appearance. Eleven lodges dating to that period – four in Flanders, two in Brussels and five in Wallonia – are still active today. It can be said that Belgian Freemasonry has its roots in the French period.

The transition to the United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815-1830) went fairly smoothly in the lodges, partly due to the prudence of the main board and the Grand Master, Prince Frederik. The Grand Orient of the Netherlands granted the southern lodges reasonable autonomy under a provincial administrative grand lodge. Additionally, Crown Prince William, later King William II, was admitted to a Brussels lodge. The relationship with Orange-Nassau is close and, apparently, the two princes felt more comfortable in the French tradition-oriented Freemasonry than in the Dutch.

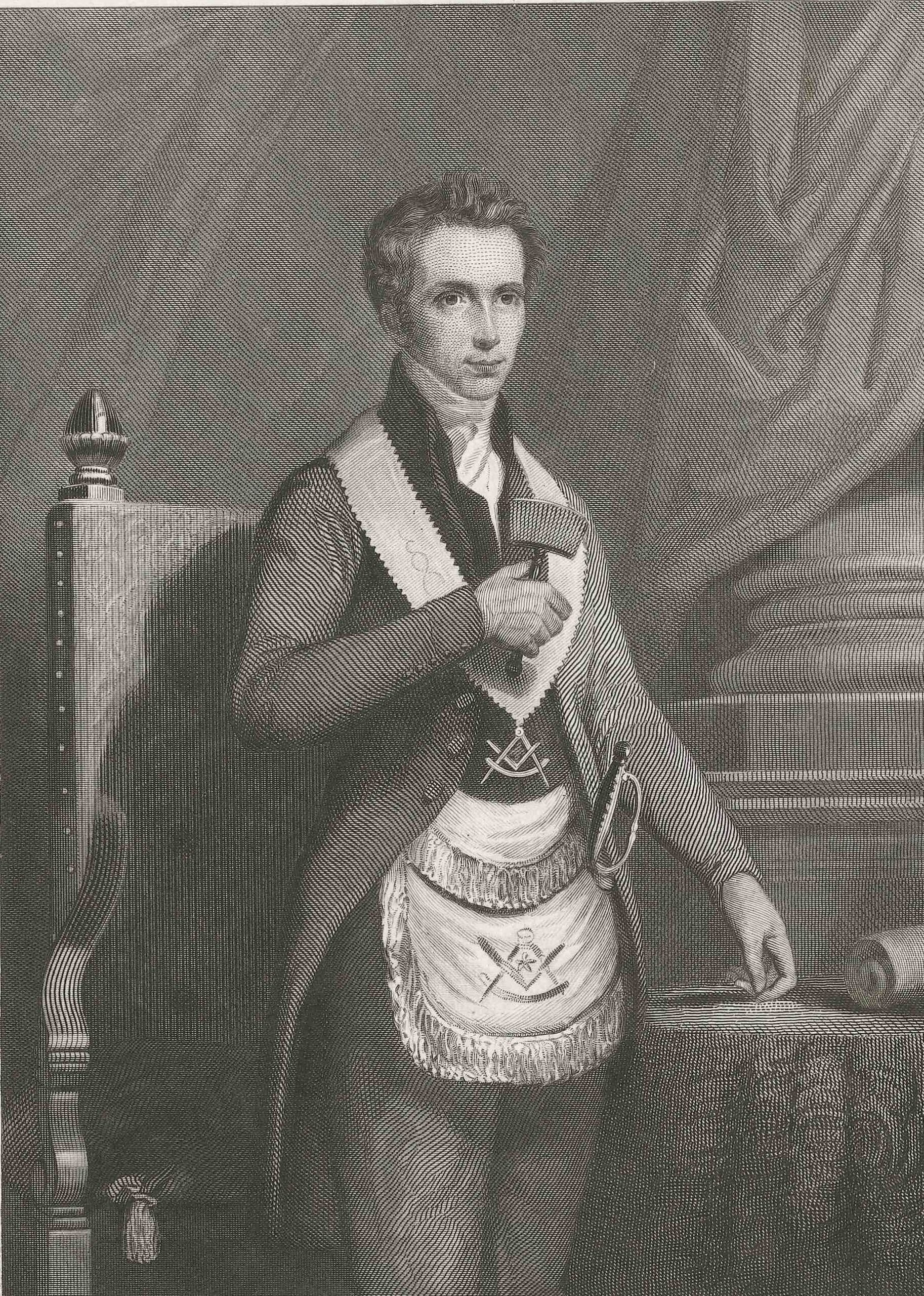

Johannes Philippus Lange, after Valentijn Bing, Portrait of Prince Frederik of the Netherlands, 1845, Rijksmuseum

Johannes Philippus Lange, after Valentijn Bing, Portrait of Prince Frederik of the Netherlands, 1845, Rijksmuseum© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The revolt of 1830 apparently came as a surprise in the lodges: few Freemasons were involved in that odd experiment of unionism, an alliance of Catholics with a conservative faction of the liberals. The ties were only broken after the shelling of Brussels under the leadership of Prince and Grand Master Frederik. The division is great, nonetheless. Ten lodges united under a new umbrella organisation in 1833 (the Grand Orient of Belgium); ten lodges ceased their activities, five remain members of the Grand Orient of the Netherlands, and two lodges from Liège form their own group. Supporters of Orange were not set apart by any form of cultural or political nationalism – their choices had to do with the king’s progressive vision of economic development and education. It was only after the peace treaty of 1839 that order was restored in the Belgian lodges and the Orangists resumed their places again.

The nineteenth century is definitive

To this day, the view of Belgian Freemasonry remains determined by the nineteenth century. Early on, it was confronted with an aggressive attitude from the Catholic Church. In the encyclical Mirari Vos, dating to August 1832, Pope Gregory XVI spoke out against liberalism and religious indifference. There was no royal power to curb the spread of a papal decree; thus, a considerable number of Catholics left the lodges. The latter left after a particularly harsh pastoral letter from the Belgian bishops in 1838, which went as far as to no longer allow deceased Freemasons a place in the consecrated grounds of the cemeteries. Liberals and a few Protestants were now calling the shots.

To this day, the view of Belgian Freemasonry remains determined by the nineteenth century

It is striking that the new umbrella organisation wanted to remain on amicable terms with King Leopold I (once accepted as a Freemason in Bern) but due to the negative experience with Prince Frederik’s involvement, did not consider offering him the position of Grand Master. After Frederik’s death, Dutch Freemasonry would appoint a new royal Grand Master, but on the cusp of the twentieth century, the special relationship with the royal house would also come to an end.

Septentrion lodge in Ghent

Septentrion lodge in Ghent© Michiel Hendryckx

Freemasonry in the north and south was inspired by the same new ideas of liberalism, positivism and the like. In both countries, it prioritises neutral education, but the effective translation is completely different. After 1848, the Netherlands experienced a liberal-inspired political rebirth led by Thorbecke. In Belgium, the polarisation provoked by the Catholics drives the nation’s lodges to political activism. Examples include founding the Université Libre de Belgique (later “de Bruxelles”) in response to the establishment of a Catholic university in Mechelen (later in Leuven); acknowledging discussions on social issues; supporting and, if necessary, organising, liberal constituencies. Whereas in the Netherlands public education was being expanded by liberally-inspired politics, the defense and development of public education were important matters of discussion for the lodges.

The year 1872 became an important turning point: after much discussion, the Belgian Freemasons no longer made the symbols Great Architect of the Universe and the Bible compulsory in their rituals. The French followed a few years later. The path that was then taken eventually led to the schism between the Anglo-American and the liberal traditions outlined at the beginning of this piece. With the introduction of (plural) universal suffrage in 1893, any form of political militantism gradually faded away.

From its inception, Freemasonry adopted different structures in the north and south and was built on different traditions, which can be explained by the different political and religious history of the northern and southern Netherlands. The tolerant religious climate in the Netherlands and the Catholic dominance in the south were determining factors. At the same time, the relationship between the individual members was especially amicable. So mote it be.